“Peter! C’mon! It’s 8:30 already!”

Claire was in the midst of a ritual observed by parents of teenagers for centuries, one mysteriously unchanged since the advent of the Network, and the retirement of the human race. Teenagers were amongst the people on the planet still required to be in a given place at a given time, which was curious, given that they were the least suited to perform that task.

“Can’t I just work with my math tutor today?”

“You can’t let other the people in your group do the whole project for you.”

“The other people in my group are creeps.”

“Peter!”

“They don’t know the difference between entropy and potential energy.”

“Well, that’s why they need you there.”

It was a small mercy that Claire was spared the trial of suggesting a lunch option. Peter would be home for lunch today, and even those days he was at school all day, lunch was provided by the Food Network. She just needed to make sure Peter was dressed and standing at the curb for a podcar, and…

“Have you eaten anything?” she asked.

“No.”

Claire sighed.

“Get dressed,“ she said, and then, after Peter had closed the door to his room. “Madge, can we have a blueberry bran muffin and an orange for Peter to eat in the podcar.”

“Certainly,” the family’s domestic AVA answered.

Claire turned to her daughter, sitting with her husband at the counter, finishing up her eggs. Judy was not yet a teenager, and so much easier to get out the door. Claire had had a thought in her mind to say something when she turned, but forgot about it as she watched Judy chattering happily to James.

Judy paused to push in another forkful. James looked up and smiled to see Claire watching them.

“I’m going ride with Judy to school and go on to the golf club from there. Do you want to come up to the club for lunch. Around 1?”

“That would be good,” said Claire. “I wanted to talk to you about Jill.”

Claire walked over to James so she wouldn’t be talking to him from across the room.

“She’s thinking about having a baby,” she said quietly.

“What?! Didn’t she skip the parenting courses in high school?”

“Yeah. She was the never-going-to-have-kids party girl then,” said Claire.

“Good Lord. How old is your sister? 27?”

Before Claire could answer Peter’s bedroom door opened and Peter emerged, clothed.

“There’s a muffin and an orange by the door,” said Claire.

She might have been telling him there would be thumbscrews and the rack before the beheading.

“Look,” she said, “you can spend the afternoon with the math tutor AVA, but you need to get out and work with people.”

“Why? Where is it written I have to work with people? Especially those people.”

“Why must you always ask that question? Do you think the answer is going to change?”

“I’m waiting for someone to give me a sensible answer.”

Claire tugged lightly at Peter’s sweater, smoothing out where it was bunched at the shoulders.

“You might think now that you’re better off on your own, but you’re not. People need people.”

“Are all those people going to disappear if I stay in today?”

“Oh Peter. Just get going would you?” she said, and then.

“The muffin!” she shouted, as his long legs hurried him out the door. He spun, grabbed it from the table by the front door, and was gone.

***

About a block from home, Peter chucked the muffin out the window of the podcar, then instructed it to stop at a café where he grabbed a chocolate doughnut. Over the last few months he had determined that he could pass up his breakfast for a doughnut once a week. He wondered if the Network had told his parents. If it had, they had not said anything about it.

By the time he got to school he regretted having tossed the muffin. He was still hungry, but there was no time to eat now.

He made his way to the lab bench. Eva and Siobhan, the two girls at the table, hated him, scarcely able to exchange two words with him without rolling their eyes. And Chris, in the three weeks their lab group together, he did not think he had heard Chris say two words. Chis would stare off into space while the other three did the work, except when Peter was doing all the work himself.

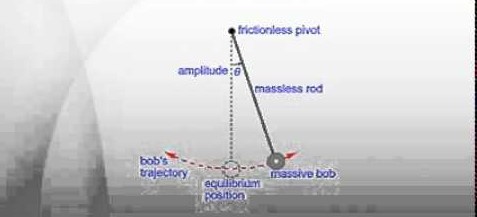

The project for the day was pendulum motion, experimenting with different weights, different lengths, higher and lower amplitudes, and Peter was dreading it. He had started some preliminary research the night before and got caught up in the subject, spending three hours on it. He had grasped the concept of potential energy converting to kinetic energy, the point of this experiment, within a few minutes, and moved on to the entropy implications of stretchable strings and pivots with friction and air resistance, material well beyond this day’s experiments.

How was he supposed to spend the morning with these three and a vastly oversimplified pendulum experiment without screaming?

Eva looked up at Peter as he approached.

“So, where do we start?” she asked.

“How about by looking at the instructions you have open on the screen,” Peter responded.

Eva rolled her eyes.

There were about 100 14- and 15-year olds in the lab, divided up into groups of three and four. There was no teacher. The Education Network provided instructions on the screens, with resources to explore for extra help available. On this day there were three adults in the room, education volunteers. There were as many as six on some days, occasionally none at all.

It was not as if the room was without supervision if there were no adults present. The Network observed and recorded the behaviour of every student.

These students had been wearing a Network watch from the time they were born. The key function of the watch initially was to monitor the health of the baby. Crib death rates had dropped to virtually zero in watch-wearing babies. There was little interaction between baby and Network. Parents provided all the care for infants in their first year, with the Network providing the necessaries to the parents.

Over that first year, however, the Network was getting to know each baby as an individual, measuring how different stimuli induced particular physiological responses. When, as a toddler, the child started talking, a personal AVA was introduced, and the Network would experiment with different conversational approaches, measuring responses and rewarding positive behaviour with known, desired, individualized stimuli.

The Network would come to know what the child wanted and needed better than the child did. For privacy reasons, no human could directly access this information.

This process was well understood by the parents, who relied on the Network for child-rearing advice. It was also understood the system was not perfect. The children could play the system, learning what was the absolute minimum to get what they wanted. Adolescents, as they had for millennia, often acted out in unpredictable ways that were clearly against their interests, and that threw all the Network algorithms into a spin.

But this rarely played out as seriously disruptive behaviour in the classroom. Each student’s AVA had enough carrot and stick strategy at hand to prevent that.

Peter could not resist over the next hour pointing out how their measurements did not match the theory because the pendulum bob was swinging through air, the string bent and stretched and twisted, and rubbed where it was connected at the top.

The girls looked at him blankly; Chris stared out the window.

Peter brought up on the screen a site he had found the previous night where you could do virtual pendulum experiments. You could start with a pendulum that perfectly converted potential energy to kinetic energy, then add air resistance, stretchable strings, friction at the pivot. The site revealed the minute temperature changes in the string.

“That’s entropy, right?” said Eva.

Now it was Peter’s turn to stare blankly.

“Look it,” Chris interjected before Peter could respond. “I’m sure this is all amazing, but can we just get this done and get out of here? Like I need to know what entropus is?”

“Entropy,” said Peter.

“Are you not getting me?” said Chris. “I don’t care. Let’s just get it done.”

“I know,” said Siobhan, clearing the screen. “Just tell me what to put in the report.”

***

Peter was home an hour early. His sister was still at school and his parents out at lunch. He still hadn’t had anything to eat since the chocolate doughnut.

“Madge,” he said. “Can I get a 12-inch, cold-cut sub?”

“Certainly,” said Madge. “It’s been a long morning for just a blueberry muffin. You should get up earlier so you can have more for breakfast.”

“You know I didn’t eat the blueberry muffin, don’t you.”

“Of course. But I make you think about it more if I pretend even for a moment I don’t.”

“Just shut up and make me a sandwich.”

“Blah, blah, blah,” said Madge.

Cold-cut sub was a bit of a misnomer for what Madge delivered to him. There was no cutting of meat involved. The protein in the sub was individually pressed from flesh extracted from beetles by exquisitely-designed machines next to the beetle farm in the basement. This particular sandwich was made up from three different flavours of beetle wafer. While even someone accustomed to eating actual slices of meat would have trouble telling the difference by looking at the sandwich, one bite would be plenty.

Peter, who had rarely eaten mammal meat, savoured every chew.

As he ate he called up Matt, his math tutor AVA. While he had grasped the basic entropy concepts in pendulum motion, he had found the math to be beyond him.

“So this is calculus, right?” asked Peter.

“Yes, it is,” said Matt. “We’ve poked at that a little before, but you weren’t ready to pursue it seriously.”

“Well, I’m ready now,” said Peter.

Peter did not pause to consider why he should spend his afternoon studying calculus. He was vaguely aware he had a distant cousin who had been one of the last working human physicists. He had met her at his Great-Great Aunt Sarah’s 100th birthday party a few years ago. Peter had been already considered gifted at math and his mother had made a point of introducing the two of them. The woman, whose name he couldn’t remember, had said some words of encouragement, but Peter was too shy to continue the conversation.

This vague awareness did not equate to anything like inspiration. It did not occur to him that he might make some important discovery with this talent. No one encouraged that belief, or even suggested such a thing was possible. He was merely curious, and filling the time.

Eva was at that moment filling the time playing a virtual reality empire-building game. She was seated on a throne in her virtual world. An advisor spread a map out before her and presented the latest information from explorers on the frontier. They considered advantageous positions for a new settlement.

Siobhan was playing softball with friends, balancing on her toes between first and second base, her palms itching for the feel of the ball as the pitch went in. Then, as the ball was knocked out to centre field, sprinting out to cut off the throw, her thoughts on preventing the first base runner from making it home on the play.

Chris was disconnected from the Network. The Network noted he was in the 100th percentile for disconnected time in his age group. Chris did not want to talk about it: not to his parents, and not to his AVAs.

Peter was soon engaged with a collection of tutorials, games and virtual reality experiences introducing the principles of differential calculus. The Network, which was good at a lot, had 30 years experience of teaching math and was better at that than most things.

After 90 minutes, sensing Peter’s mental fatigue, Matt wrapped up the last VR experience and said, “Time for some fresh air.”

“What about a game of Strange Effusions?” countered Peter.

“Nope,” said Matt.

Peter sighed, took off his head set, which had gone dark, and plunked down the stairs to the ground floor.

He had almost the whole afternoon before him.

“Randomize left or right,” he said, when he reached street level.

“Right.”

Peter turned right, and repeated the request for random direction at the next intersection, and the next, and the next. He was soon not asking for directions or even pausing at intersections, the Network giving his random directions as he approached choices. He found himself passing his home a mere five minutes later. He considered going back in, but carried on.

An hour later his random wanderings took him into the old town. He loved the variety of the buildings here, in comparison with the standardized, efficiency housing in the suburbs. Some of the homes, a striking number of them whole buildings designed for a single family, had been retrofitted for modern living. Others were set aside as museums, representing particular years in that city. Some of those could be walked through casually and others could be booked for holidays, providing a more in-depth experience of life in that era.

Random directions directed Matt into a 2014 house. He glanced into the front room as he passed. A large piece of hardware, apparently required for the screen on the face of it, was hanging on the wall. On the screen a smartly-dressed man sucked on a burning stick, looking moodily off into the middle distance.

Peter wandered into the kitchen, where he bathed in unfamiliarity. He pulled on some of the doors. In one a light came on revealing a box, empty except for a glass disk. A waft of cold air passed over his arm when he opened the door to a larger box. This one was not empty: cartons and jars were scattered over the shelves. There seemed to be food in the jars.

A friend of his had holidayed in a 1994 house. He had described preparing food in a kitchen much like this one. Every day they had to make breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Peter didn’t get it.

On the way out he spotted a replica of an almost century-old mobile phone sitting on the front table. He cradled it in his hand, marveling at the thought of having to deal with such a tiny, physical screen, instead of the virtual screens available to him almost anywhere.

The house’s AVA suggested he hold down the button and ask the phone a question.

“What is a refrigerator?” he said.

“I found these resources on the web for you,” the phone responded.

Peter shook his head, put the phone back on the table, and walked out of the house.

“Almost dinner time,” said Madge’s voice, after a few more random turnings. “A podcar will be by in two minutes to take you home.”

And at the next random turn the podcar was there. Peter climbed in and was driven home to join his family.